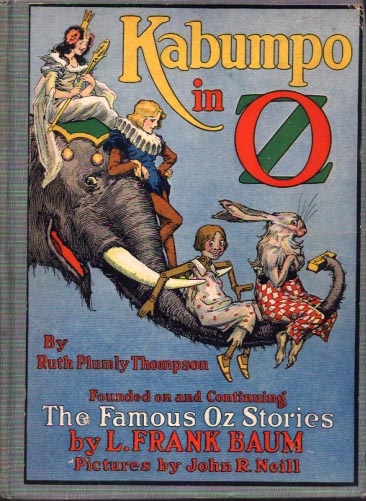

In Kabumpo in Oz, Ruth Plumly Thompson began to find her own distinctive Oz voice.

She also found her own elegant elephant.

Kabumpo in Oz begins with a literal bang, as a scrumptious pink birthday cake explodes at the birthday party of one Prince Pompadore of Pumperdink. (If you are wondering why immortal people who never age need birthday parties…well, Thompson explains that in Oz you age, or not, as you choose, but that shouldn’t stop you from the fun of having a birthday.) Not only are all of the guests tragically covered in cake and frosting, which is just terrible when you are an elegant elephant wearing fine silk court robes (and if you are wondering why an elephant is wearing fine silk robes, I can only say, well, it’s Oz) but they are also greeted with a terrifying message. The Prince must marry a Proper Fairy Princess within a week, or his entire kingdom will disappear forever.

The question is, what, precisely, is a Proper Fairy Princess? Kabumpo, the Elegant Elephant, ornament of the court, the only one to stay calm in the crisis, suggests that the Proper Fairy Princess must, of course, be Ozma, the little fairy ruler of Oz. The King, Queen and Prime Pompus, perhaps concerned with what they’ve heard about Ozma’s leadership abilities (or lack thereof), and also concerned about the distance between Pumperdink and the Emerald City, instead suggest that the prince wed Princess Faleero, a hideously ugly old fairy. Determined not to let the prince suffer such a hideous fate, Kabumpo kidnaps the prince and heads to the Emerald City. As in all good fairy tales, they run into Complications. For yes, this tale begins as a fairy tale, in the classic “prince must find and win the princess” style—although, admittedly, it’s not often that said princes need to be kidnapped by elephants.

Said complications include the rather terrifying village of Rith Metic, a place constructed of—gulp—math books and numbers that walk and talk (I sense Thompson and I had similar feelings about math in school); Ilumi Nation, where candles walk and talk; and returning villain Ruggedo, now fully established as the Oz’ series ongoing Big Bad. Well, in this case, initially a Small Bad, living with a chattering rabbit named Wag who has a thing for socks.

Ruggedo has been, delightfully enough, spending his time rewriting his personal history on six small rocks and playing dreadful songs on the accordion. The sound is enough to send Wag fleeing for his socks and his wooden doll, Peg Amy. (We all have our needs.) Soon enough, however, Ruggedo mistakenly brings Peg Amy to life and turns himself into a giant—with Ozma’s palace balanced precariously on his head. Shrieking, he flees, with his giant steps swiftly taking the palace, and its residents, out of Oz. Ozma, of course, is incapable of rescuing her own palace (did you expect any other response at this point?) leaving it up to Kalumpo, Prince Pompadore, Peg Amy, and Wag (mourning his socks) to mount a rescue.

The book focuses on the trappings of royalty, and on people concerned with finding—or maintaining—their proper place in society. Characters continually obsess over appearances and proper behavior for their rank and condition. To be fair, this is partly because one of them has been turned into a giant with a palace stuck on his head. It would worry anyone. But the concerns of others often seem overwrought, or even inappropriate. In the middle of a desperate chase to save Ozma, the Elegant Elephant is so worried about the damaged state of his robes that he has Peg Amy fix them. The prince assumes that no one will believe he is a prince after he has burned his hair. As most of Ozma’s palace falls into an enchanted sleep, the Tin Woodman…carefully polishes himself.

Peg Amy, the living wooden doll, takes these fears to the most heartbreaking level. She may have memories of another life, and a gift for making devoted friends, and a kindly heart. But none of that, she fears, makes up for being just a doll:

“Why, I haven’t even any right to be alive,” she reflected sadly. “I’m only meant to be funny. Well, never mind!”

Other Oz characters, however constructed, had always taken their right to live for granted. Indeed, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Patchwork Girl had often insisted that their materials made them superior to “meat” people, since they did not have to eat or sleep. This reasoning never occurs to Peg Amy. Unlike the Patchwork Girl, who refused to enter the subservient role planned for her, Peg Amy unhappily accepts her servant position, and decides to justify her existence through work, with the traditional feminine tasks of mending and sewing, by the less traditional methods of helping the group save Ozma and her friends, and by helping Pompa marry Princess Ozma.

None of this goes as well as planned. Although Pompa, noting that all princesses must marry the princes who rescue them, does propose to Ozma, to her credit, the Ruler of Oz does not think that getting rescued is a great basis for a marriage, and refuses him.

Kabumpo in Oz may have begun as a traditional fairy tale, but it does not quite end like one. Not only does the prince not win his expected princess, but the tale also requires a second, somewhat muddled, ending. And in the end, Kabumpo in Oz is less about the prince, and more about the lessons Peg Amy and Kabumpo learn about appearances and true royalty. And if it is somewhat jolting to read Thompson’s suggestion that Peg Amy earns her happy ending by embracing a more traditional, subservient role, after several books rejecting this pathway for women in Oz, Thompson adds the counter examples of Glinda (masterful as always) and Ozma, both refusing to accept the places fairy tales would place them into.

Kabumpo in Oz is not flawless. As I mentioned, the ending is muddled, and in an odd scene midway through the Wizard of Oz appears, advising everyone to be calm, smiling as if he knows exactly what is going on and will explain it momentarily—and then disappears for the rest of the book. I have no idea what this scene is doing in the book; its truncated nature reads like an authorial or editorial error. But this is a considerably more enjoyable introduction to Thompson’s Oz books, with their myriads of tiny kingdoms filled with young princes and princesses tailor-made for adventure. (She would later claim that Oz has 705 of these kingdoms, theoretically giving her material for 705 books, had she been so inclined or physically capable.)

I don’t want to leave without mentioning the eponymous character, the pompous but kindly Elegant Elephant, who would return in later books, and the hilarious scenes with the Runaway Country. Tired of waiting to be discovered, the Runaway Country has decided to step up—literally, on ten large feet—and run off to find settlers of its own who can develop it into a “good, modern, up-to-Oz kingdom”—never hesitating for a moment to kidnap our heroes in this quest. I admit that I had an environmental twinge or two while rereading this passage, along with an urge to shout, “No! Run away before you get developed and over-developed!” But things may be different in Oz, and in a book exploring the need to submit to your role in life, it’s rather delightful to find a land stubbornly refusing to do so.

Mari Ness hasn’t been kidnapped by any Runaway Countries yet, but she rather likes the idea. She lives in Central Florida.